Scientific Insights on Menopause Transition: Key Findings

Reading time 14 min

Reading time 14 min

Over the years, researchers around the world have conducted key studies that have shaped how we understand our major life transitions. Research spans from hormone replacement therapy (HRT) to the long-term health effects of menopause.

Understanding scientific insights on menopause transition is essential for navigating your health choices with clarity and confidence. I’ve broken down some of the most influential studies, explaining their methods, major findings, and the controversies that followed.

What are the key scientific insights on menopause transition?

Scientific research on menopause transition reveals crucial findings about hormone therapy, cardiovascular risks, bone health, and symptom management, helping women make informed health decisions.

Let’s start with the most influential study to date: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI). This was a massive study launched in 1993, involving over 160,000 postmenopausal women aged 50 to 79 (average 63) in the United States.

The study focused on finding ways to prevent and manage common chronic conditions in postmenopausal women, such as heart disease, cancer, and bone fractures due to osteoporosis. The WHI included three clinical trials, which explored hormone therapy, diet modifications aimed at lowering fat intake, and the benefits of calcium and vitamin D supplements.

The main study primarily focused on how hormone replacement therapy (HRT) prevented cardiovascular diseases. It also examined the risks and benefits related to cancer, fractures, and other age-related illnesses1, 2, 3.

The WHI was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), considered the gold standard of research. Participants were randomly assigned to receive combined oral estrogen-progestin therapy, oral estrogen-only therapy (for women who had undergone hysterectomies), or a placebo.

In 2002, the study made headlines when it was announced that women on combined HRT had a higher risk of breast cancer, heart disease, and strokes. These findings caused HRT use to drop dramatically around the world. However, data showed that combined estrogen-progestin therapy increased the absolute risk only by ~0.1% per year for strokes, heart attacks, and breast cancer.

The findings were based mostly on older women who were many years postmenopausal when they started HRT. However, women aged 50–59 who took estrogen alone or estrogen-progestin did not have a higher risk of stroke and actually showed positive signs for heart disease, overall survival, and general health outcomes. After 18 years of follow-up, neither group of women aged 50–59 had higher death rates from any cause, including heart disease or cancer.

The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) ran from 2005 to 2012. It aimed to answer questions left by the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) about when and how safely women should start hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as they enter menopause. KEEPS focused on whether starting HRT early in menopause could offer heart and brain benefits without the risks seen in older women10, 11.

KEEPS was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (RCT) that enrolled 727 women aged 42–58 within three years of menopause who had no history of heart disease. Women were randomly assigned to one of three groups: low-dose oral estrogen, transdermal estrogen (a patch), or a placebo.

Women receiving estrogen also took progesterone to balance the hormone effects. For four years, researchers tracked heart health markers, cognitive function, and menopause symptoms like hot flashes and sleep problems. They closely examined arterial health using carotid artery ultrasounds and coronary artery calcium scores to detect changes in cardiovascular health.

KEEPS found that starting HRT early did not raise the risk of heart disease and even improved some heart health markers, like lowering arterial stiffness in women using the skin patch. It also showed that HRT reduced hot flashes and night sweats, helped with sleep, and boosted overall quality of life. There was no drop in cognitive function, suggesting that early HRT did not negatively impact brain health in newly menopausal women.

KEEPS offered promising results, but its four-year follow-up left questions about long-term safety, especially regarding breast cancer risk, which might take longer to appear. Some experts also believe that KEEPS may not fully apply to women with existing heart risks since it mainly studied a healthy group. A 14-year follow-up study found that HRT had no lasting positive or negative effects on heart or metabolic health12.

The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS), conducted from 1993 to 1998, was one of the first major clinical trials to assess hormone replacement therapy’s (HRT) impact on heart disease in postmenopausal women with already existing coronary heart disease. The study enrolled 2,763 women at an average age of 66.7 years in the USA4, 5, 6.

HERS was a randomized placebo-controlled trial (RCT) to explore the potential benefits and risks of HRT. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either combined oral estrogen-progestin therapy. The women were followed for several years to determine whether hormone therapy could reduce their risk of heart attacks or other cardiovascular events.

The initial results, published in 1998, found that hormone therapy did not reduce the risk of heart attacks or death from heart disease. In fact, during the first year of the study, women taking HRT had an increased risk of heart attacks, though this risk leveled out in subsequent years. A follow-up study, HERS II, extended the follow-up period to 6.8 years and confirmed that HRT provided no overall cardiovascular benefit.

HERS challenged the widely held belief that HRT could protect women from heart disease. The study showed that starting HRT in women who already had coronary heart disease could actually increase their risk of heart attacks in the short term. These findings led to significant changes in how HRT was prescribed, particularly for women at risk of cardiovascular disease.

The Penn Ovarian Aging Study (POAS) began in 1996 and continued for over two decades. It focused on tracking hormonal changes during the menopausal transition and their effects on mood and physical health. The study enrolled approximately 436 generally healthy women aged 35-47 at baseline and followed them through the stages of perimenopause and postmenopause7, 8, 9.

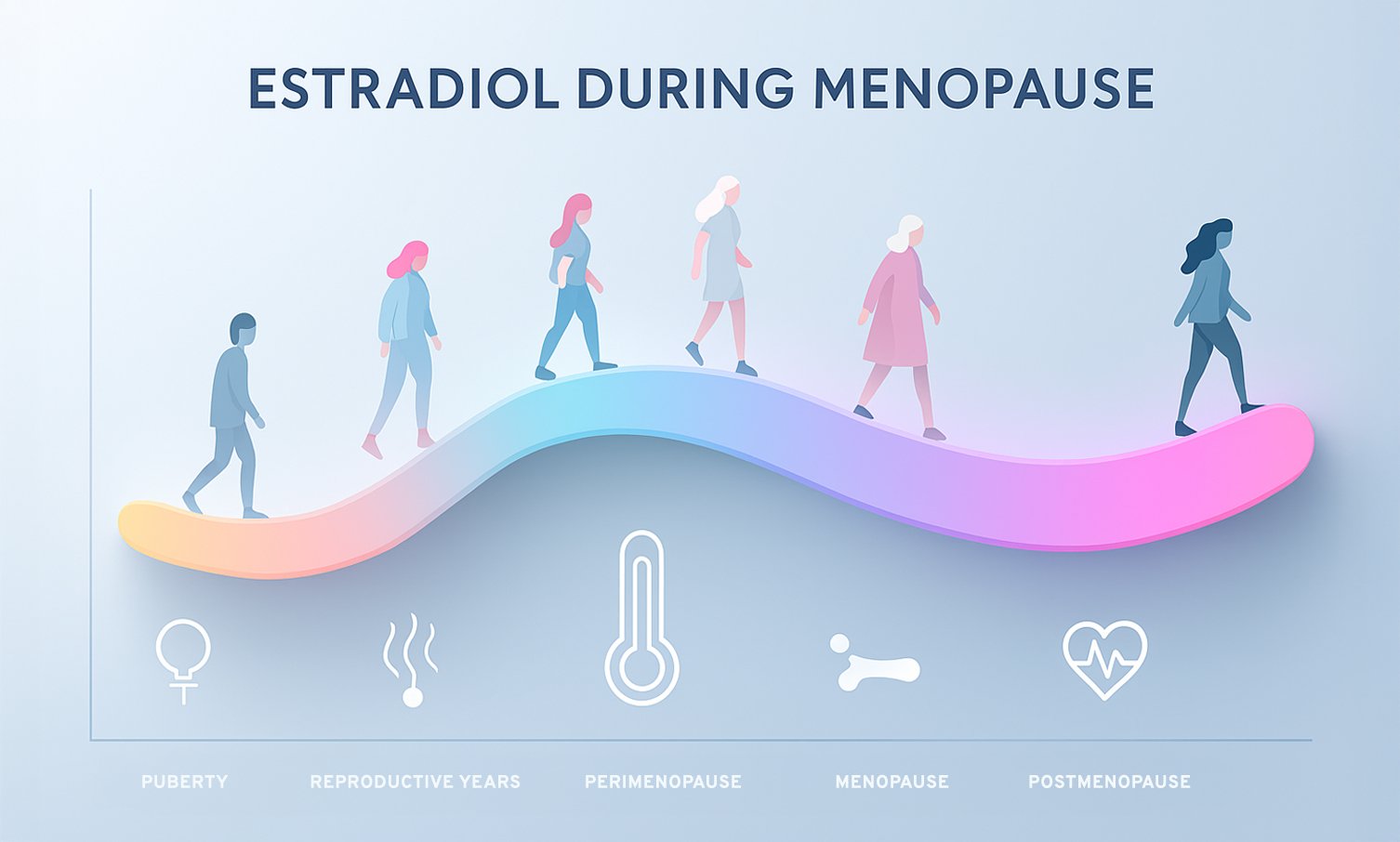

POAS is an observational longitudinal cohort (group) study, meaning it followed the same group of women over time. The focus was on naturally occurring changes during the menopausal transition rather than testing any treatments or interventions. The researchers measured hormone levels such as estradiol, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH) through regular blood tests. Alongside this, they collected data on the women’s mood, cognitive function, sleep patterns, and other symptoms.

The study found that hormonal fluctuations, particularly declining estradiol and rising FSH, were associated with significant mood disturbances, including increased rates of depression and anxiety during the menopausal transition. Women with a history of depression were especially vulnerable to mood swings during perimenopause. The study also contributed to the understanding that menopause involves complex hormonal interactions, not just a drop in estrogen.

While the study provided crucial insights into how hormonal shifts affect mood, some argue that it didn’t fully account for the role of lifestyle, environmental, and psychological factors, which also contribute to mood changes during menopause. Despite this, POAS remains a key study in the field for its focus on the biological aspects of the menopausal transition.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) began in 1996 and is an ongoing study that provides insights into how midlife aging, including menopause, affects women’s health. SWAN is one of the most comprehensive studies on menopause, following over 3,000 women aged 42-52 from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds, including African American, Hispanic, Chinese, Japanese, and Caucasian women in the USA. This diversity has made SWAN unique in exploring how menopause and aging affect different groups13, 14.

SWAN is a longitudinal cohort study, a type of observational study that follows participants over time. To be eligible for the study, women needed to have a uterus and at least one ovary, and they couldn’t be using hormone therapy at the start. Researchers used annual physical exams, blood tests, and questionnaires to collect data on a wide range of health measures, including hormone levels, bone density, cardiovascular health, mood, cognition, and quality of life.

SWAN has uncovered key insights into how menopause symptoms and health risks vary by race and ethnicity in the USA. For example, African American women were found to experience more intense vasomotor symptoms (hot flashes and night sweats) and enter menopause slightly earlier than Caucasian women, while Asian women had fewer vasomotor symptoms but were at higher risk for bone density loss. SWAN also highlighted that menopause impacts a wide range of health areas, including cardiovascular health, metabolic function, and mental well-being.

SWAN demonstrated that midlife is a key time to start healthy habits and preventive care. The study shows that midlife health isn’t fixed; it can be improved, which can positively affect health and well-being in later years. By showing that menopause is not a “one-size-fits-all” experience, SWAN has contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the menopausal transition.

SWAN’s findings have expanded our knowledge of menopause. However, there is some debate about the cause of the racial and ethnic differences observed. Are these differences mostly due to biology, or do social and environmental factors, like access to healthcare or income, play a bigger role? Also, while SWAN focuses on hormone changes, some critics think it should look more closely at lifestyle factors that affect midlife health, such as physical activity, smoking, or alcohol use.

The Melbourne Women’s Health Project (WHAP) started in 1991 in Australia. It is the longest-running medical research project focused on women’s health, especially heart and brain health during midlife and later years. It has given us important insights into how menopause affects women’s physical and mental health over time. This study has followed a group of women from perimenopause to postmenopause, observing changes in symptoms, hormone levels, and health. Its findings have helped us understand menopause’s impact on heart health, bone density, and overall quality of life15, 16.

This is a population-based cohort study, a type of observational study. The Melbourne Women’s Health Project enrolled approximately 438 women and conducted regular follow-ups over decades to assess changes in hormone levels, menopausal symptoms, and health markers such as bone density and heart health.

Data was collected through physical exams, blood tests, and detailed questionnaires, allowing researchers to observe the natural course of menopause and its impacts without intervention. The study has produced over 150 peer-reviewed articles that have contributed to national and international guidelines on women’s health.

A key finding from the Melbourne Women’s Health Project is that severe menopausal symptoms, like hot flashes and night sweats, are strongly tied to lower estradiol levels. The study also emphasized that lifestyle choices, such as staying active and having a healthy diet, help ease menopausal symptoms. Importantly, it showed that menopause affects heart health, with heart disease risk increasing as estrogen levels drop. This research also linked menopause to bone density loss, underscoring the need to manage osteoporosis risk in the postmenopausal years.

The Melbourne Women’s Health Project showed that lifestyle can help manage menopausal symptoms. However, some critics say it may not consider the challenges women face in controlling these factors, especially in midlife when work, family, and other responsibilities are demanding. Also, the study focused on a relatively similar group of women.

This raises questions about how well the findings apply to more diverse populations. Despite these limitations, the Melbourne Women’s Health Project remains important for understanding menopause’s impact on women’s health.

The major menopause studies from the 90s gave us invaluable insights and raised as many questions as they answered. They confirmed that menopause isn’t a neat, predictable process.

Research around hormone replacement therapy (HRT) offered data that was both reassuring and alarming, especially with conflicting findings around timing, health risks, and benefits. These studies showed menopause is highly personal, shaped by our unique biology, backgrounds, and lifestyle choices.

One thing that stands out is how these studies painted broad strokes, giving us a “big picture” but often missing individual nuances. They emphasized that menopause isn’t just a collection of symptoms or something to “get through.” It’s a significant biological shift that deserves as much understanding as any other stage of life.

Today, research continues, but disappointingly, we’re not seeing large-scale studies like those from decades ago. While smaller studies are adding pieces to the puzzle, there’s still a need for more comprehensive research that reflects diverse experiences. Menopause science is far from settled, and there’s still much to learn about this complex journey we all navigate in our own ways.

Dr. Jūra Lašas

1.

Neves-e-Castro, M. et al. Results from WHI and HERS II – Implications for women and the prescriber of HRT. (2002) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5122(02)00214-1

2.

Scott, I. Interpreting risks and ratios in therapy trials. (2008) https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2008.008

3.

Manson, J. et al. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Health Outcomes During the Intervention and Extended Poststopping Phases of the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trials. (2013) https://doi.org/10.1001%2Fjama.2013.278040

4.

Speroff, L. The heart and estrogen/progestin replacement study (HERS). (1998) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-5122(98)00104-2

5.

Wells, G. et al. The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. (1999) https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199915060-00001

6.

Byington, R. et al. Effect of Estrogen Plus Progestin on Progression of Carotid Atherosclerosis in Postmenopausal Women With Heart Disease: HERS B-Mode Substudy. (2002) https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000033514.79653.04

7.

Freeman, E. et al. Longitudinal pattern of depressive symptoms around natural menopause. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2819

8.

Freeman, E. et al. Hormones and menopausal status as predictors of depression in women in transition to menopause. (2004) https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.62

9.

Freeman, E. et al. Methods in a longitudinal cohort study of late reproductive age women: the Penn Ovarian Aging Study (POAS). (2016) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-016-0014-2

10.

Miller, V. et al. The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS): what have we learned? (2019) https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001326

11.

Gleason, C. et al. Effects of Hormone Therapy on Cognition and Mood in Recently Postmenopausal Women: Findings from the Randomized, Controlled KEEPS–Cognitive and Affective Study. (2015) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001833

12.

Kantarci, M. et al. Cardiometabolic outcomes in Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study continuation: 14-year follow-up of a hormone therapy trial. (2023) https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000002278

13.

Avis, N. et al. THE STUDY OF WOMEN’S HEALTH ACROSS THE NATION (SWAN): FROM MIDLIFE ONWARD. (2019) https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz038.1287

14.

Khoudary, S. et al. The menopause transition and women’s health at midlife: a progress report from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). (2019) https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001424

15.

Szoeke, C. et al. Cohort profile: Women’s Healthy Ageing Project (WHAP) – a longitudinal prospective study of Australian women since 1990. (2016) https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-016-0018-y

16.

Guthrie, J. et al. The menopausal transition: a 9-year prospective population-based study. (2004) https://doi.org/10.1080/13697130400012163