Rock‑Solid: How Exercise Builds Better Bones in Menopause

Reading time 7 min

Reading time 7 min

Bones don’t get as much attention as abs or biceps—but exercise for bone health during menopause is crucial. I often hear women say, “My doctor told me I’m developing osteoporosis—what can I actually do about it?” The fear is understandable, especially when you hear alarming statistics about bone fractures after menopause.

When estrogen levels drop our bones start losing density at an accelerated rate. We are not powerless though! Your bones are living, dynamic tissues that respond remarkably well to the right kind of movement, even during and after menopause1, 2.

What’s the best exercise for bone health during menopause?

The most effective bone-building exercises include weight-bearing movement, resistance training, and plyometrics. These forms of exercise apply mechanical stress that signals your bones to grow stronger and denser.

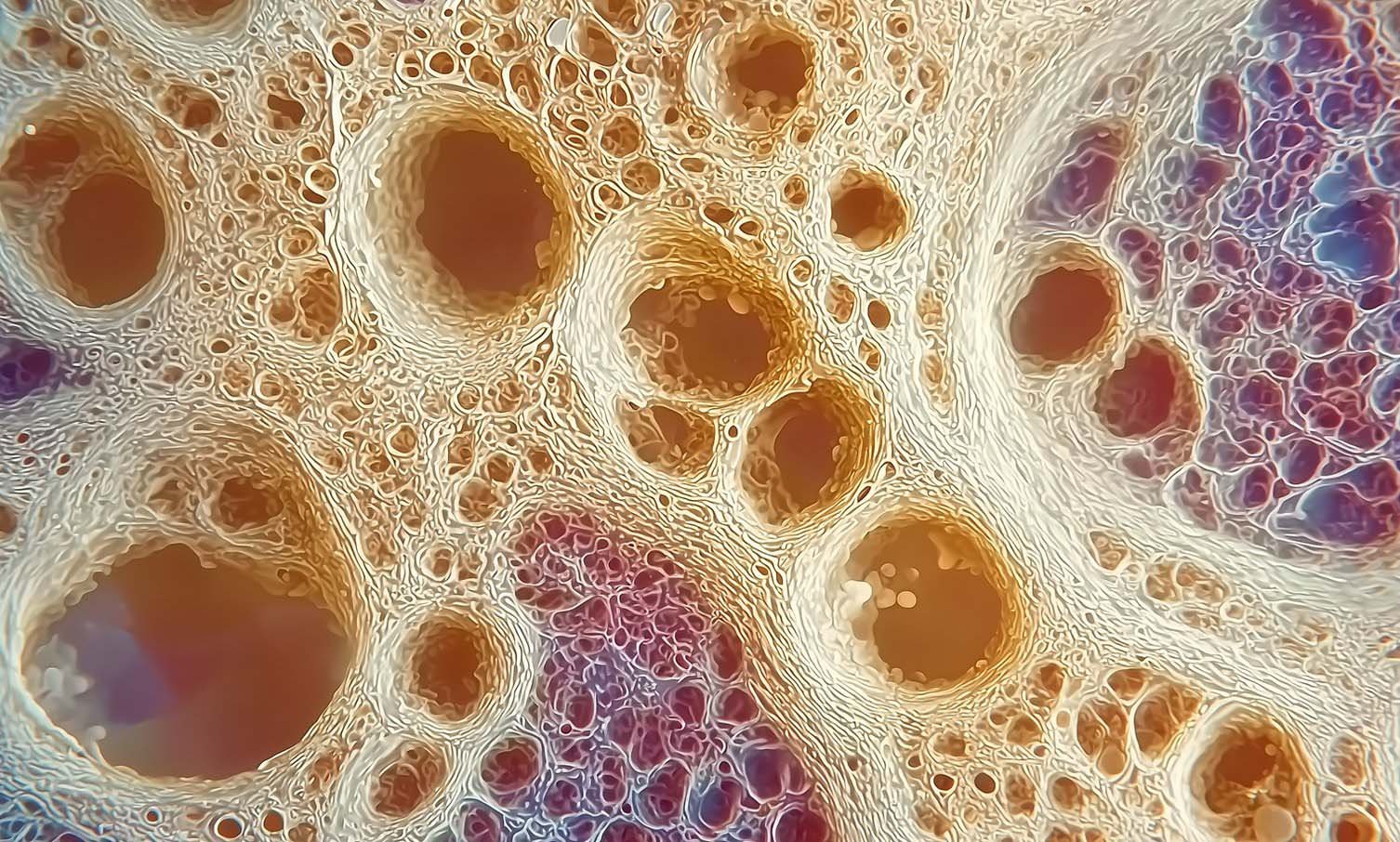

Your bones aren’t static sticks of chalk. They’re living tissue constantly being reshaped by two cell crews working around the clock:

Osteoclasts—the demolition team that breaks down old bone tissue.

Osteoblasts—the construction crew that builds new bone tissue.

In our younger years, the builders work faster than the demolition crew, allowing us to hit peak bone mass around age 30. In a healthy, pre-menopausal body, these teams work in perfect balance, essentially replacing your entire skeleton roughly every ten years1.

During menopause, declining estrogen speeds up the osteoclasts while slowing down the osteoblasts, causing bone mineral density (BMD) to plummet, especially in the spine, hips, and wrists2.

Exercise stimulates bone formation by creating mechanical stress that signals bones to become stronger and denser. Mechanical stress from exercise sends electrical-chemical signals through your bones. Whether it’s the ground reaction force from brisk walking or the pull of a resistance exercise, that stress tells your osteoblasts, “Hey, we need more scaffolding here!” The result? More bone gets laid down exactly where the stress occurred3.

This is why bones respond specifically to the type of stress you place on them, following what scientists call Wolff’s Law: bones adapt to the loads placed upon them. It’s biology’s way of ensuring your skeleton can handle whatever demands you place on it4.

The stakes become much higher during menopause:

Accelerated bone loss

You can lose up to 10% of your total bone mass within the first five years after your final period. That’s a decade’s worth of normal aging compressed into five years5.

Increased fracture risk

Hip fractures double every ten years after age 50, and carry a sobering one-year mortality rate of approximately 20%6.

Posture and pain

Vertebral compression fractures (condition where one or more of the small bones in your spine become compressed or collapse) contribute to forward stoop and chronic back pain that nobody wants.

Many doctors don’t emphasize enough the studies which consistently show that women well past menopause can still add bone mass when exercise intensity is adequate7.

Not all exercise is created equal for bone health. Your bones need specific types of stress to trigger the remodeling response8, 9:

Not so helpful:

The optimal “dose” for bone health is more specific than general fitness recommendations10:

Frequency

At least 3-4 days per week for bone-specific benefits. Your bones need regular, consistent stimulus to maintain the remodeling signal.

Progressive overload

What built your bones last month won’t be enough to keep building them this month. You need to gradually increase challenge through heavier weights, more repetitions, or higher impact.

Session duration

30-45 minutes is ideal, but even 20 minutes of focused bone-loading exercise provides benefits.

Variety

Different exercises stress bones in different ways. Combining impact, resistance, and balance training provides comprehensive bone loading.

Bone responds more slowly than muscle to exercise. This is why consistency matters more than perfection11.

“While you might feel stronger and more stable after a few weeks of training, measurable bone density changes typically take 6-12 months of consistent exercise.”

Early benefits you might notice include improved balance, better posture, increased confidence with daily activities, and better sleep quality. These improvements in quality of life might motivate continued exercise even before bone density measurements show change.

A 2025 meta-analysis of 49 randomized trials in postmenopausal women (n = 3,360) found that combined aerobic plus resistance training and resistance training alone were the most effective interventions for increasing bone mineral density(BMD)12:

Meanwhile, other exercise modalities showed no significant benefit compared to inactive control groups.

I’ll never be the woman who loves burpees, but I do love the idea of walking into my 70s without a hunched back or cracked hip. I would love you to realize: your bones are not doomed by menopause.

Yes, estrogen decline creates challenges, but exercise provides a powerful alternative pathway to bone strength.

Every weight-bearing step, every resistance exercise, every balance challenge is an investment in the woman you’ll be when you are 70, 80, 90…

Remember, “use it or lose it” isn’t a threat—it’s simply biology.

Dr. Jūra Lašas

1.

Hadjidakis, D. et al. Bone Remodeling. (2007) https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1196/annals.1365.035

2.

Khosla, S. et al. Effects of sex and age on bone microstructure at the ultradistal radius: a population-based noninvasive in vivo assessment. (2006) https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.050916

3.

Wang, L. et al. Mechanical regulation of bone remodeling. (2022) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-022-00190-4

4.

Ruff, C. et al. Who’s afraid of the big bad Wolff?: “Wolff’s law” and bone functional adaptation. (2006) https://doi.org/10.1002/AJPA.20371

5.

Chapurlat, R. et al. Longitudinal Study of Bone Loss in Pre- and Perimenopausal Women: Evidence for Bone Loss in Perimenopausal Women. (2000) https://doi.org/10.1007/s001980070091

6.

Sing, C. et al. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post‐Fracture Treatment, and All‐Cause Mortality. (2023) https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4821

7.

Wallace, B. et al. Systematic Review of Randomized Trials of the Effect of Exercise on Bone Mass in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women. (2000) https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223001089

8.

Gonzalo-Encabo, P. et al. Dose‐response effects of exercise on bone mineral density and content in post‐menopausal women. (2019) https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13443

9.

Xu, J. et al. Effects of Exercise on Bone Status in Female Subjects, from Young Girls to Postmenopausal Women: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. (2016) https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0494-0

10.

Mohebbi, R. et al. Exercise training and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies with emphasis on potential moderators. (2023) https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-023-06682-1

11.

Gonzalo-Encabo, P. et al. Dose‐response effects of exercise on bone mineral density and content in post‐menopausal women. (2019) https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13443

12.

Xiaoya, L. et al. Effect of different types of exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. (2025) https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-94510-3