Protein: The Building Block You Can’t Skip

Reading time 8 min

Reading time 8 min

Women’s nutritional needs shift with age. The mix of protein, carbs, and fats that worked during the reproductive years often needs adjusting in perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause. When it comes to protein needs during menopause transition, it’s usually shrouded in myths, misconceptions, or simply ignorance.

Research shows your protein requirements fundamentally change during the menopause transition, and most women aren’t getting nearly enough to support their changing biology.

How much protein do you need during menopause?

Most women need more than they think. As estrogen declines, protein becomes essential for maintaining muscle, bone strength, and metabolism. Aim for 1.0–1.6g of protein per kg of body weight daily.

Protein is your body’s building material. It’s made of amino acids that help repair and rebuild muscles, bones, hormones… Unlike carbs and fat, protein can’t be stored for later use. Your body breaks it down daily into amino acids to build and repair.

Excess protein is broken down and excreted rather than stored for future use. Therefore, you need a steady supply. If you don’t get enough, your body starts pulling from your own muscle to get what it needs1.

There are 20 amino acids that make up the proteins in your body, each with a unique structure and role. Of these, 9 are called essential amino acids—your body can’t make them, so you must get them from food.

The remaining 11 are non-essential, meaning your body can produce them on its own. When it comes to building and repairing muscle, leucine is especially important—it acts as a trigger for muscle protein synthesis. Research shows, if you do not get enough leucine, muscle will not grow2.

Different protein sources have different amino acid profiles. Animal proteins (like meat, fish, eggs, and dairy) are considered “complete” because they contain all 9 essential amino acids in good amounts.

Most plant proteins are “incomplete”, meaning they lack one or more essential amino acids. You will need to combine different plant foods (like beans and rice) to fill the gaps. That’s why quality matters: it’s not just about how much protein you eat, but which amino acids it provides.

While perimenopause and postmenopause are distinct phases hormonally, there are no substantial differences in protein requirements between them. What matters most is that estrogen gradually declines, reducing your body’s ability to build and maintain muscle.

As a result, you may find it harder to hold onto muscle mass and easier to gain fat. Maintaining muscle mass is crucial—it supports metabolism, helping you manage weight more easily, and protects your bones by keeping them strong3.

Your body has a built-in drive to eat enough protein each day—this biological instinct is called the protein leverage effect. It means you naturally aim for a certain amount of protein, no matter how much fat or carbs you’re eating.

Research confirms that postmenopausal women tend to eat less protein by increasing fat and carbs in their diets. If your meals are too low in protein, your body pushes you to keep eating until that protein target is met.

The result? You end up eating more overall calories, often without realizing it. Simply put, the lower your protein intake, the higher your total calorie consumption tends to be, increasing your risk of unwanted weight gain4.

General dietary guidelines suggest 0.8 g protein per kg body weight for all adults (e.g. 70 kg/154 lb woman should eat a minimum of 56 grams/2 oz of protein a day). However, emerging science reveals that postmenopausal women need significantly more, potentially 50% higher, to maintain muscle mass, bone density, and metabolic function as estrogen levels decline.

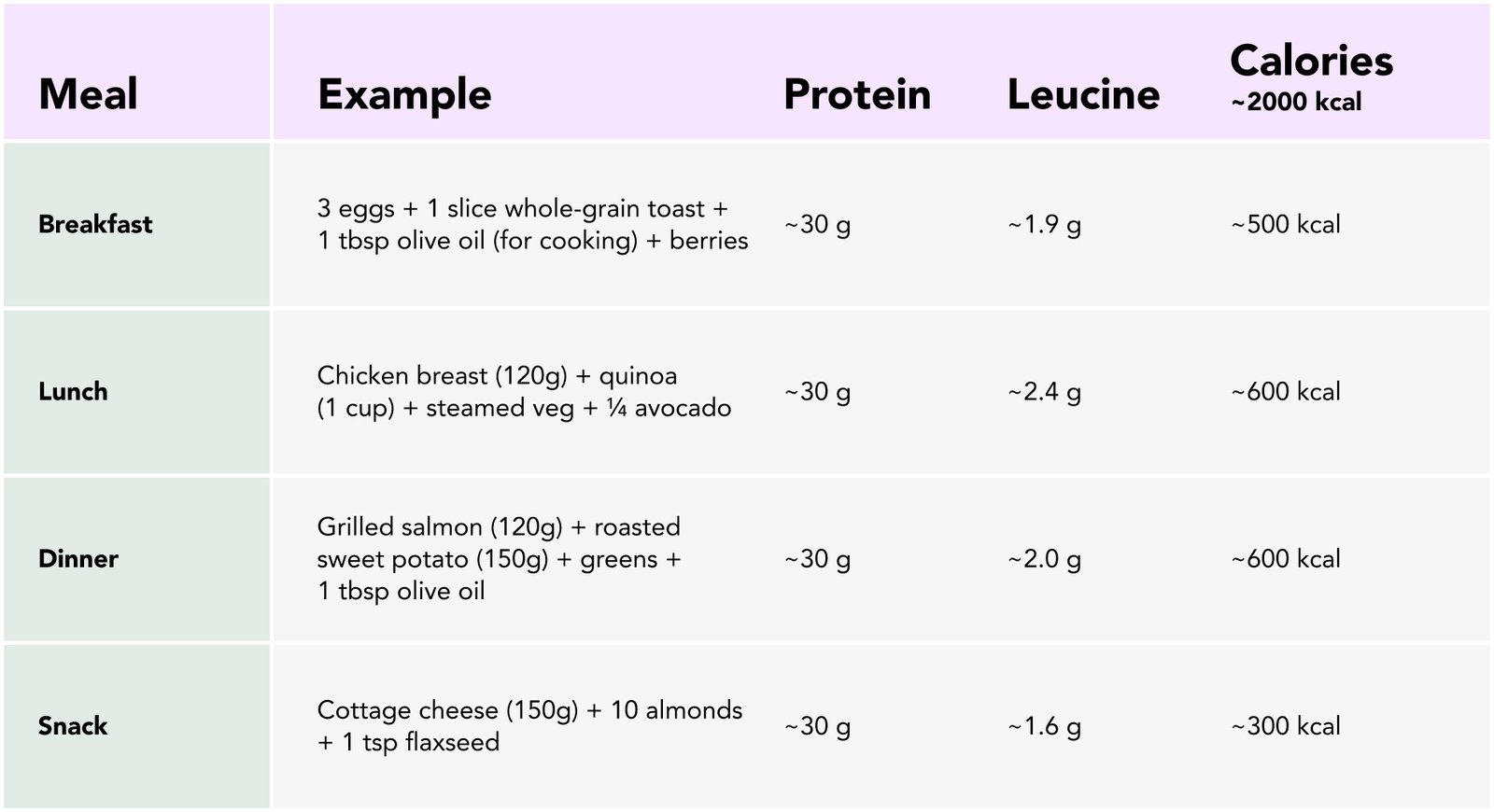

Many scientists recommend 1.0–1.6 grams of protein per kg body weight for the women in menopause transition. So, a 70 kg/154 lb woman should eat 70-112 grams/2.5-4 oz of protein a day5, 6.

Research shows that even distribution could be more effective than consuming the same total amount in fewer, larger portions. It’s still debated whether you need a set amount of protein at each meal but there’s no doubt that getting enough over the course of the day is essential7.

Most importantly, eating more protein without combining it with resistance training, will not result in meaningful muscle growth9. Enough protein will help maintain the muscle to a certain extent, but we all want to get healthier as we age, so we have to hit those weights!

Myth–High Protein Diets Are Dangerous for Women

Social media often portrays high-protein diets as exclusively for bodybuilders or potentially harmful for women. However, research shows that protein intakes up to 2.0g per kg body weight are safe for healthy women and may be beneficial during menopause10.

When I first learned about the increased protein needs during menopause, I was skeptical. Like many women, I’d internalized the idea that more protein meant more calories, which meant weight gain.

But the research is clear: adequate protein during menopause is about muscle and health preservation. The protein leverage effect is real. If you don’t give your body the protein it’s craving, it will drive you to eat until you get it, often in the form of processed foods that provide calories without the amino acids you actually need.

I’ve seen too many women try to solve menopause symptoms by eating less, when what they really need is to eat differently. More protein, distributed throughout the day, combined with resistance exercise, isn’t just about maintaining muscle—it’s about vitality as you age.

Dr. Jūra Lašas

1.

Hoerter, J. et al. Biochemistry, Protein Synthesis. (2023) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545161/

2.

Church, D. et al. Stimulation of muscle protein synthesis with low-dose amino acid composition in older individuals. (2024) https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1360312

3.

Rizzoli, R. et al. The role of dietary protein and vitamin D in maintaining musculoskeletal health in postmenopausal women: a consensus statement from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO). (2014) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.005

4.

Simpson, S. et al. Weight gain during the menopause transition: Evidence for a mechanism dependent on protein leverage. (2023) https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17290

5.

Black, K. et al. The Impact of Protein in Post-Menopausal Women on Muscle Mass and Strength: A Narrative Review. (2024) https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia4030016

6.

Matkin-Hussey, P. et al. The Impact of Protein in Post-Menopausal Women on Muscle Mass and Strength: A Narrative Review. (2024) https://doi.org/10.3390/physiologia4030016

7.

Hudson, J. et al. Protein Distribution and Muscle-Related Outcomes: Does the Evidence Support the Concept? (2020) https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12051441

8.

Church, D. et al. Stimulation of muscle protein synthesis with low-dose amino acid composition in older individuals. (2024) https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1360312

9.

Wätjen, W. et al. Analysis of combinatory effects of free weight resistance training and a high-protein diet on body composition and strength capacity in postmenopausal women – A 12-week randomized controlled trial. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnha.2024.100349

10.

Sun, Q. et al. The different association between fat mass distribution and intake of three major nutrients in pre- and postmenopausal women. (2024) https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304098