Sleep and Menopause – Everything You Need to Know (But Were Too Tired to Ask)

Reading time 8 min

Reading time 8 min

Sleep weaves through every aspect of our lives: physical health, mood, memory, and even how we respond to stress. The pioneering sleep researcher Allan Rechtschaffen famously noted: “If sleep does not serve an absolutely vital function, then it is the biggest mistake the evolutionary process has ever made.”1

Sleep is essential for everyone. Hormonal changes can make it harder to get the rest you need during menopause. Understanding sleep and menopause is the first step toward fixing it.

Why does menopause affect sleep?

Hormonal changes during menopause – especially the drop in estrogen and progesterone – disrupt the body’s natural sleep regulation. This can lead to night sweats, insomnia, and poor-quality rest.

I cover the most significant management tools for improving sleep and overall health in separate articles under Healthy Body & Mind and Exercise & Nutrition.

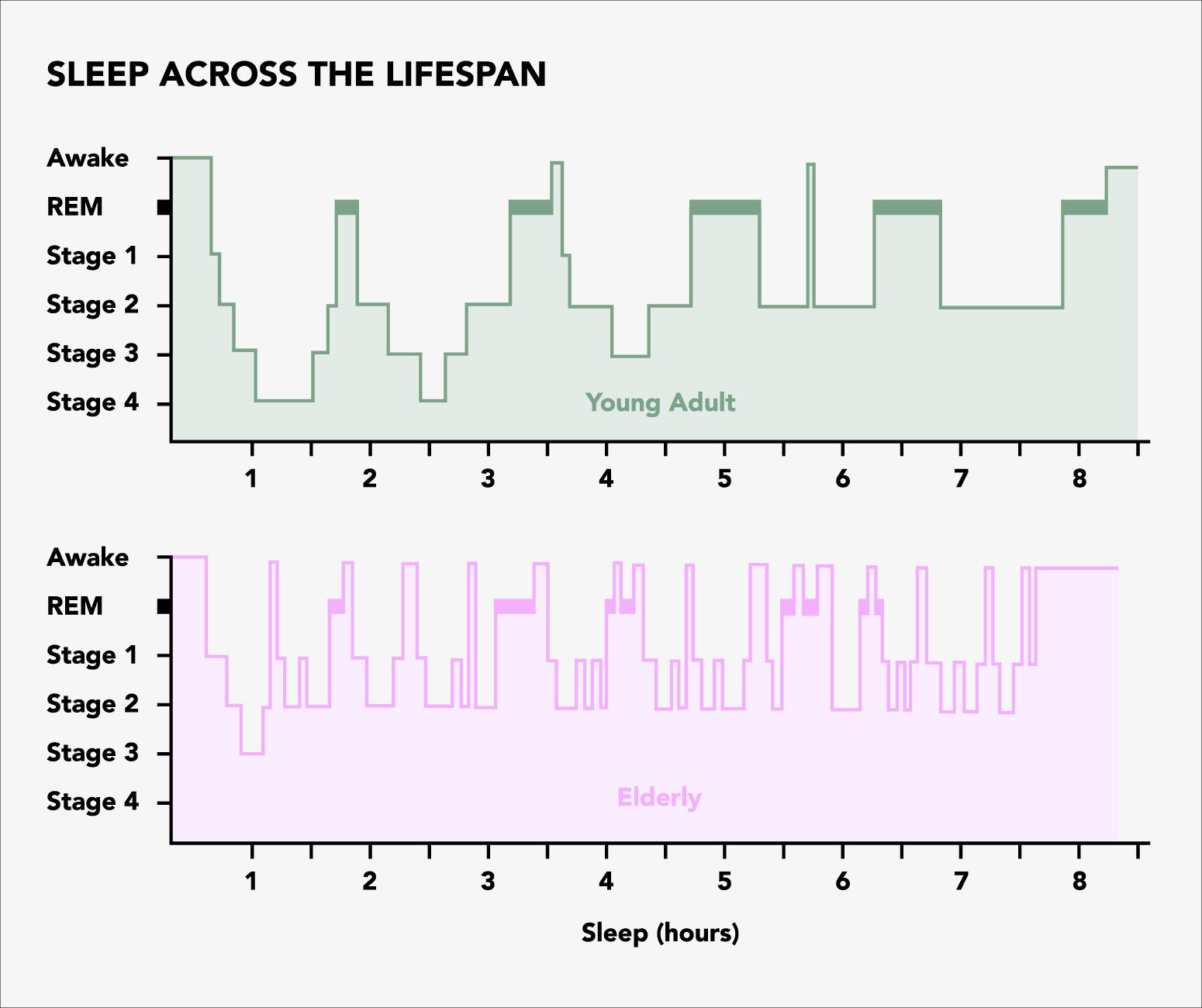

Sleep isn’t just “switching off.” It’s an active, carefully regulated biological process that helps our bodies repair and our minds recharge. There are two main types of sleep – non-rapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep – which alternate in cycles of about 90 minutes throughout the night2, 3.

REM Sleep (Stage 4): About 90 minutes after you fall asleep, REM sleep begins. Brain activity is similar to wakefulness, and this is where most dreaming occurs. Your eyes dart back and forth under closed lids, but your muscles remain temporarily paralyzed to prevent acting out those dreams. REM sleep is key for memory consolidation, mood regulation, and learning.

While everyone needs restful sleep, women often face unique challenges during the menopausal transition. Sleep disturbances affect roughly 50% of women4, 5. Hormonal shifts – particularly dropping levels of estrogen and rising follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) – are linked to frequent awakenings, difficulty staying asleep, and changes in sleep architecture.

In addition, decreasing estrogen and progesterone levels impact the brain’s sleep centers, making it harder to maintain deep, restorative sleep9.

It’s fascinating that the menopause transition affects sleep cycles. Deep sleep (Stage 3), crucial for physical recovery, becomes shorter. This stage is when the body repairs tissues, strengthens the immune system, and supports overall health.

Losing time in this stage can leave you feeling less refreshed10. Women often wake up more during the night and shift out of deep sleep more easily, leading to disrupted and fragmented sleep11.

Decreased estrogen is directly linked to sleep problems, though the exact reasons aren’t fully understood yet. Estrogen plays a key role in regulating sleep by activating brain areas responsible for starting and maintaining sleep6, 7.

It also helps regulate night time body temperature for better sleep8. Meanwhile, progesterone acts directly on neurons, boosting GABA release (a calming neurotransmitter) that promotes non-REM sleep.

Getting quality sleep isn’t just about feeling rested – it’s foundational to your health, especially during menopause. Hormonal shifts can throw your sleep off balance, but the ripple effects go much further.

From your metabolism to your mood, nearly every system in your body is impacted when sleep goes sideways. So, why does it matter? Let’s break it down.

A lack of quality sleep sets off a chain reaction that affects your entire body. One of the most noticeable changes is in appetite regulation. Insufficient sleep boosts levels of ghrelin, a hormone that signals hunger, and dampens leptin, the hormone telling you you’re full. The result? Stronger cravings, more snacking, and overeating, which can easily translate to weight gain if this cycle continues unchecked12, 13.

Over the long term, these changes contribute to a higher risk of obesity and impaired glucose metabolism, which means your body struggles to maintain stable blood sugar levels14.

Beyond metabolic risks, poor sleep has been associated with elevated blood pressure, adding hypertension to the list of potential health concerns15. Chronic sleep deprivation may also open the door to cardiovascular problems – though direct evidence in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women is limited and mainly comes from broader population studies.

Still, these findings raise the possibility that improving your sleep could help guard against heart disease and related conditions16, 17.

Just as your body falters without rest, so does your mind. Persistent sleep difficulties can exacerbate or even trigger mental health conditions. Depression is strongly linked with poor sleep, and the relationship works both ways: sleepless nights can lead to low mood, and existing depression can further undermine sleep quality, creating a vicious cycle that’s tough to break18, 19.

Anxiety also tends to flare when sleep is disturbed, fueling nighttime worries and making it even harder to settle down at bedtime20, 21.

The reach of poor sleep extends into your daily routine, making everyday tasks feel like uphill battles. Chronic fatigue saps your energy, reduces motivation, and can make it difficult to stay focused or productive at work and at home22.

Over time, the combined toll on physical and mental health can erode life satisfaction. When you’re constantly tired, grappling with mood issues, or worried about long-term health consequences, it’s harder to feel content or fully engaged in life’s experiences23.

Research shows that women often report more sleep problems than what objective measurements reveal. Many women describe struggles like insomnia, frequent awakenings, and non-restorative sleep, but tools like polysomnography (a comprehensive sleep study) often capture fewer or milder disruptions than they report24, 25.

This gap suggests that hormonal changes, particularly declining estrogen and progesterone, along with mood disorders like anxiety and depression, shape how women perceive their sleep. Symptoms such as hot flashes and night sweats further contribute to discomfort, even if they don’t significantly alter measurable sleep stages.

Combining subjective experiences with objective data is crucial to fully understand and address the sleep challenges perimenopausal and postmenopausal women face.

The complexity of sleep – especially during the menopausal transition – is both fascinating and frustrating. Hormones that once supported good sleep now leave you restless, overheated, and awake at odd hours. Sleep is not just “rest” but an active, hormone-sensitive process that influences every corner of your health.

From trying HRT to exploring CBT-I or experimenting with melatonin, the key is to approach sleep with patience and openness. Small steps like improving your sleeping environment, addressing hot flashes, or managing stress can yield meaningful improvements.

Even if the cause-and-effect puzzle of menopause and sleep still feels like a chicken-or-egg scenario, knowing that interventions exist and can help – offers hope.

Just remember, you’re not alone in this journey. As research evolves, we’ll find more tailored solutions. Until then, reclaiming sleep means working with your changing biology rather than fighting against it. Better nights can lead to better days, and that’s worth every bit of effort.

Dr. Jūra Lašas

1.

Rechtschaffen, A. Current perspectives on the function of sleep. (1998) https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.1998.0051

2.

Carskadon, M. et al. Chapter 116 – Monitoring and Staging Human Sleep. (2005) https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-72-160797-7/50123-3

3.

Agnew, H. et al. The displacement of stages 4 and REM sleep with a full night of sleep. (1968) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.1968.tb02811.x

4.

Xu, Q. et al. Examining the relationship between subjective sleep disturbance and menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000240

5.

Blümel, J. et al. A multinational study of sleep disorders during female mid-life. (2012) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.011

6.

Hadjimarkou, M. et al. Estradiol suppresses rapid eye movement sleep and activation of sleep-active neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area. (2008) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06142.x

7.

Smith, P. et al. Estradiol influences adenosinergic signaling and nonrapid eye movement sleep need in adult female rats. (2022) https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab225

8.

Freedman, R. et al. Core body temperature during menopausal hot flushes. (1996) https://doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(16)58328-9

9.

Polo-Kantola, P. et al. Aetiology and Treatment of Sleep Disturbances During Perimenopause and Postmenopause. (2001) https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200115060-00003

10.

Kalleinen, N. et al. The temporal relationship between growth hormone and slow wave sleep is weaker after menopause. (2012) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2011.05.010

11.

Lampio, L. et al. Sleep During Menopausal Transition: A 6-Year Follow-Up. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsx090

12.

Spiegel, K. et al. Sleep loss: a novel risk factor for insulin resistance and Type 2 diabetes. (1985) https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00660.2005

13.

Gran, L. et al. Effect of Experimentally Induced Sleep Fragmentation and Hypoestrogenism on Fasting Nutrient Utilization in Pre-Menopausal Women. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvab048.1575

14.

Pilnik, S. Sleep Disorders in Perimenopausal Women and Metabolic Syndrome, is that True? (2018) http://dx.doi.org/10.32474/OAJRSD.2018.01.000109

15.

Bruyneel, M. Sleep disturbances in menopausal women: Aetiology and practical aspects. Maturitas. (2015) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.04.017

16.

Wolk, R. Sleep and Cardiovascular Disease. (2005) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2005.07.002

17.

Tamura, K. et al. An interesting link between quality of sleep and a measure of blood pressure variability. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.14160

18.

Meerlo, P. et al. Chronically Restricted or Disrupted Sleep as a Causal Factor in the Development of Depression. (2015) https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2015_367

19.

Franzen, P. et al. Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. (2008) https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2008.10.4/plfranzen

20.

Freedman, R. et al. Sleep disturbance in menopause. Menopause. (2007) https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3180321a22

21.

Guidozzi, F. Sleep and sleep disorders in menopausal women. (2013) https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.753873

22.

Andenæs, R. et al. Associations between menopausal hormone therapy and sleep disturbance in women during the menopausal transition and post-menopause: data from the Norwegian prescription database and the HUNT study. (2020) https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905-020-00916-8

23.

Baker, F. et al. Sleep problems during the menopausal transition: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. (2018) https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S125807

24.

Xu, M. et al. Comparison of subjective and objective sleep quality in menopausal and non-menopausal women with insomnia. (2011) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.003

25.

Young, T. et al. Objective and Subjective Sleep Quality in Premenopausal, Perimenopausal, and Postmenopausal Women in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. (2003) https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/26.6.667