The Truth About Weight Gain (And How to Beat It)

Reading time 8 min

Reading time 8 min

Weight gain during menopause is one of the most frustrating challenges many of us face1. Studies show that the rate of obesity among American women rises sharply after age 40, affecting 65% of women aged 40–59 and 73.8% of women over 602, 3. The trend is similar in Europe – obesity rates here increase with age4, 5, 6.

Why do women gain weight during menopause?

Weight gain during menopause happens because of hormonal changes, slower metabolism, muscle loss, stress, and poor sleep. Declining estrogen shifts fat storage to the belly and makes it harder to burn calories. Aging and lifestyle changes also contribute, making weight management more challenging during this life stage.

The good news? Understanding why this happens is the first step toward regaining control. Let’s explore the biological and lifestyle factors contributing to weight gain during perimenopause and menopause, and practical strategies for managing it.

I cover the most significant symptoms and management tools in detail in separate articles under Healthy Body & Mind and Exercise & Nutrition.

On average, women gain about 1.5 pounds (0.7 kg) per year during their 40s and 50s, regardless of their initial body size or race/ethnicity6, 7, 16, 17. You might notice your clothes fitting tighter around the waist or that losing weight isn’t as easy as it used to be.

Weight gain and changes in belly fat are common as we move from our reproductive years into menopause. In fact, visceral fat – the deeper belly fat around your organs – can increase by as much as 44% during postmenopause8, 9, 10.

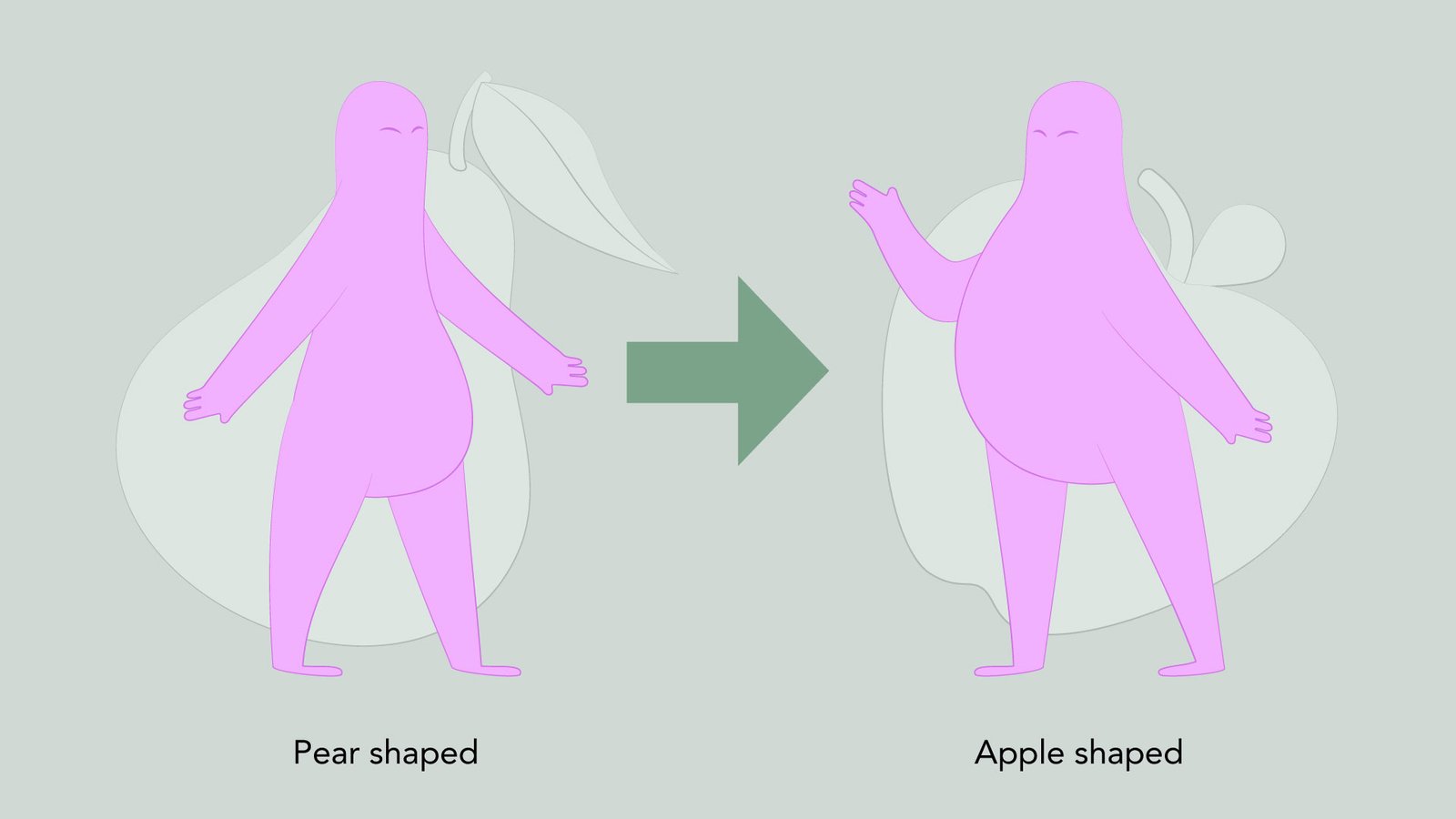

As estrogen levels drop during perimenopause, your body undergoes a series of changes that make weight gain feel almost unavoidable. One of the biggest shifts is an increase in total body fat, particularly around the belly. Most of us are used to carrying weight in our hips and thighs – the classic “pear-shaped” figure. However, lower estrogen levels direct fat storage to the midsection, creating an “apple-shaped” appearance11, 12, 13.

It’s all estrogen, baby!

This shift isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s driven by changes in how hormones like estrogen and testosterone interact. With less estrogen, testosterone becomes more influential, encouraging fat to accumulate around the abdomen (just like in men!)12. On top of estrogen decrease, estrogen receptors in fat tissue behave differently during menopause transition. There are two types of estrogen receptors: ERα and ERβ. During menopause, the ratio shifts – ERα decreases while ERβ increases – further encouraging fat to settle around the belly14, 15.

“I’m doing the same things: eating healthy and exercising, why isn’t it working anymore?”

And it’s not just about fat – your lean body mass (which includes muscles) also declines, partly due to estrogen decrease. Research shows that losing muscle mass, a condition called sarcopenia, slows down your metabolism and reduces the calories you burn throughout the day, making it harder to maintain your weight10, 12, 16, 17, 18.

“Why is a muffin top forming? I’ve always been so lean!”

Estrogen also plays a big role in how your body uses energy and regulates hunger. It helps suppress appetite by reducing signals from hormones like neuropeptide Y (NPY) and ghrelin, which tell your brain you’re hungry.

“Look at that belly fat, where is it coming from?”

At the same time, it boosts sensitivity to leptin, the hormone that signals your brain you’re full. As estrogen declines, these systems become less effective, leaving you feeling hungrier or less satisfied after meals19, 20.

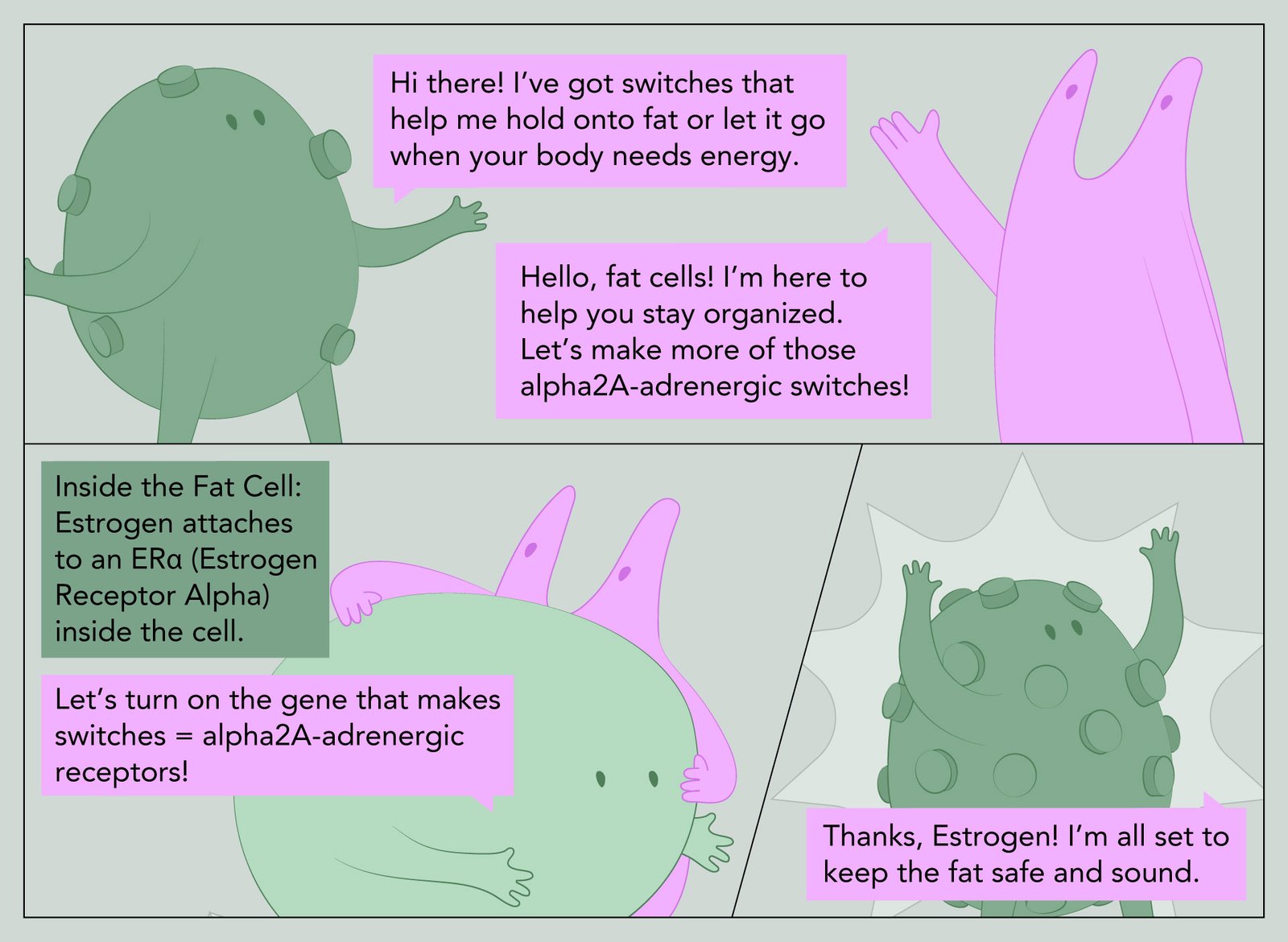

Estrogen influences how your body stores and uses fat by increasing the activity of alpha2A-adrenergic receptors in fat cells. These receptors act like tiny “brakes” on fat breakdown. When there are more of these receptors, it becomes harder for your body to release stored fat for energy.

Estrogen, through its estrogen receptor ERα, boosts the number of these receptors, which helps control where fat is stored and how it’s used. This connection is part of why fat tends to be stored differently in women, especially during reproductive years.

While hormonal changes are a major driver of weight gain during menopause, they’re not the only ones. Several other factors – from natural aging to lifestyle shifts – can add to the challenge. Understanding these influences can help you take a more complete and empowered approach to managing your weight.

As we age, due to the loss of lean mass, our metabolic rate slows down, meaning our bodies burn fewer calories throughout the day. Research shows that women’s activity levels also decline with age, often by half from 4 years before menopause to when menopause begins21, 22. This decrease in physical activity, combined with a slower metabolism, creates the perfect storm for weight gain.

Stress adds to the mix. Cortisol, the hormone associated with stress and metabolism, increases significantly during late perimenopause, particularly around 7 to 12 months before and after the menopause23. Some studies link higher cortisol levels to increased belly fat and obesity in postmenopausal women, although not all research agrees on this connection24, 25, 26. Regardless, stress often leads to unhealthy eating habits, emotional eating, and reduced physical activity, making weight management even more challenging21.

Depression, mood swings, and anxiety – common during perimenopause – are often tied to less movement and overeating. The most consistent behavioral factor contributing to weight gain during the menopause transition is a reduction in leisure-time physical activity. With stress, social obligations, and lack of time piling on, staying active becomes harder, which inevitably leads to weight gain27, 28, 29.

Sleep problems are another critical piece of the puzzle. Poor sleep disrupts appetite and metabolism, leading women to eat more, often at night (right, ladies?!). It’s a vicious cycle: less sleep lowers levels of hormones (like leptin and peptide YY) that help you feel full while raising ghrelin, the hunger hormone. Stress and fatigue from sleepless nights drive unhealthy coping mechanisms like overeating, drinking alcohol, or skipping exercise. Together, these factors make weight gain during perimenopause an uphill battle30, 31, 32.

Managing weight gain during menopause often requires a multi-layered approach. Medical treatments, lifestyle adjustments, and mindset shifts can all play a role. Let’s look at some of the most effective strategies

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can be a helpful option for managing weight during menopause. It’s been shown to reduce belly fat, improve blood sugar and insulin levels, and support lean muscle, making it easier to maintain a healthier body33, 34. Women on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) often notice a reduction in belly fat and other metabolic benefits35. However, HRT isn’t for everyone. It’s essential to consult with your healthcare provider to weigh the risks and benefits and determine if it’s the right choice for you.

Certain supplements may help support hormonal balance and weight management. Adequate vitamin D levels, for instance, may regulate estrogen synthesis and enhance the effectiveness of weight loss efforts. Women with optimal vitamin D levels – at least 30 ng/mL or 80 nmol/L – while taking supplements see better results in reducing waist size, body fat, and overall weight36, 37. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), a precursor to estrogen, might also be beneficial, but more research is needed38.

It might be a cliche, but lifestyle changes remain the cornerstone of effective weight management.

Motivational interviewing (MI) has proven to be a good tool for preventing weight gain and even achieving weight loss in perimenopausal women. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) showed that just five sessions of motivational interviewing (MI) with a health professional led to noticeable weight loss over 12 months.

Women in the MI group lost an average of 2.6 kg, while those who relied on self-directed materials saw little to no change. The success of MI comes from setting realistic goals, tracking progress, and celebrating small wins which builds confidence and supports lasting change40, 41.

Weight gain during menopause transition isn’t just about what we eat. The drop in estrogen shifts where fat is stored, making it easier for it to settle around the belly.

This hormonal change, combined with a slower metabolism, muscle loss, and lifestyle factors like reduced activity and poor sleep, creates the perfect storm for weight gain.

So, what can we do? Focus on sustainable habits that fit your lifestyle, like adding regular movement and building strength through resistance training.

Pay attention to how much and what you eat to support your goals. It’s about making small, consistent changes that add up over time. There’s no magic solution, but there are tools and strategies that can make this journey easier.

Explore more topics on my website for practical advice on diet and exercise that’s tailored to this stage of life. Together, we’ll figure this out – one step at a time.

Dr. Jūra Lašas

1.

Laine, C. et al. Menopause. (2009) https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-01004

2.

Flegal, K. et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. (2010) https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2014

3.

Eurostat News. Obesity rates in the EU. (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/ddn-20210721-2

4.

Eurostat. Overweight and obesity – BMI statistics. (2021) https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Overweight_and_obesity_-_BMI_statistics

5.

Martínez, J. A. et al. Variables independently associated with self-reported obesity in the European Union. (1999) https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-200

6.

Lewis, C. et al. Weight gain continues in the 1990s: 10-year trends in weight and overweight from the CARDIA Study. (2000) https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010167

7.

Pimenta, F. et al. Menopausal symptoms: do menopause type, BMI and lifestyle influence their severity? (2016) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.04.006

8.

Toth, M. et al. Menopause-related changes in body fat distribution. (2000) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06506.x

9.

Jensen, M. Role of body fat distribution and the metabolic complications of obesity. (2012) https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2008-1585

10.

Lovejoy, J. et al. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. (2008) https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.25

11.

Ley, C. et al. Sex- and menopause-associated changes in body-fat distribution. (1992) https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/55.5.950

12.

Tchernof, A. et al. Effects of the menopause transition on body fatness and body fat distribution. (1998) https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00344.x

13.

Davis, S. et al. Understanding weight gain at menopause. (2012) https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2012.707385

14.

Park, Y. et al. Age- and menopause-related differences in subcutaneous adipose tissue estrogen receptor mRNA expression. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2017.03.001

15.

Lizcano, F. Roles of estrogens, estrogen-like compounds, and endocrine disruptors in adipocytes. (2022) https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.921504

16.

Toth, M. et al. Menopause-Related Changes in Body Fat Distribution. (2006) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06506.x

17.

Choi, J. et al. Physical Activity, Weight, and Waist Circumference in Midlife Women. (2012) https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2012.673658

18.

Macdonald, H. et al. Longitudinal changes in weight in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women: effects of dietary energy intake, energy expenditure, dietary calcium intake and hormone replacement therapy. (2003) https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802283

19.

Lizcano, F. et al. Estrogen Deficiency and the Origin of Obesity during Menopause. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/757461

20.

Clegg, D. et al. Gonadal hormones determine sensitivity to central leptin and insulin. (2006) https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.55.04.06.db05-1339

21.

Kapoor, E. et al. Weight Gain in Women at Midlife: A Concise Review of the Pathophysiology and Strategies for Management. (2017) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.004

22.

Macdonald, H. et al. Longitudinal changes in weight in perimenopausal and early postmenopausal women: effects of dietary energy intake, energy expenditure, dietary calcium intake and hormone replacement therapy. (2003) https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802283

23.

Woods, N. et al. Increased urinary cortisol levels during the menopause transition. (2006) https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gme.0000198490.57242.2e

24.

Strain, G. et al. Cortisol production in obesity. Metabolism. (1980) https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(80)90043-8

25.

Yamatani, H. et al. Association of estrogen with glucocorticoid levels in visceral fat in postmenopausal women. (2013) https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318271a640

26.

Mattsson, C. et al. Estrogens and glucocorticoid hormones in adipose tissue metabolism. (2007) https://doi.org/10.2174/092986707782359972

27.

Col, N. et al. Menopause. (2009) https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-01004

28.

Sengar, M. et al. Correlation of Menopausal Status with Body Composition and Abdominal Fat Distribution. (2022) https://doi.org/10.55489/njcm.1342022431

29.

Wing, R. et al. Weight Gain at the Time of Menopause. (1991) https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1991.00400010111016

30.

St-Onge, M. Impact of sleep duration on food intake regulation: Different mechanisms by sex? (2015) https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21374

31.

Spiegel, K. et al. Leptin Levels Are Dependent on Sleep Duration: Relationships with Sympathovagal Balance, Carbohydrate Regulation, Cortisol, and Thyrotropin. (2004) https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-1003

32.

Chaput, J. Sleep patterns, diet quality and energy balance. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.09.006

33.

Gormsen, L. et al. Estradiol acutely inhibits whole body lipid oxidation and attenuates lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in postmenopausal women. (2012) https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-12-0422

34.

Chmouliovsky, L. et al. Beneficial effect of hormone replacement therapy on weight loss in obese menopausal women. (1999) https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5122(99)00037-7

35.

Munoz, J. et al. Fat distribution and insulin sensitivity in postmenopausal women: influence of hormone replacement. (2002) https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2002.59

36.

Kinuta, K. et al. Vitamin D Is an Important Factor in Estrogen Biosynthesis of Both Female and Male Gonads. (2000) https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.141.4.7403

37.

Mason, C. et al. Vitamin D3 supplementation during weight loss: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. (2014) https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.073734

38.

von Mühlen, D. et al. Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation on bone mineral density, bone markers, and body composition in older adults: the DAWN trial. (2008) https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0520-z

39.

Hunter, G. et al. Effects of resistance training on older adults. (2004) https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200434050-00005

40.

Williams, L. et al. Can a relatively low-intensity intervention by health professionals prevent weight gain in mid-age women? 12-Month outcomes of the 40-Something randomised controlled trial. (2014) https://doi.org/10.1038/nutd.2014.12

41.

Spreckley, M. et al. Perspectives into the experience of successful, substantial long-term weight-loss maintenance: a systematic review. (2021) https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2020.1862481